About the Project

The Democracy Principle website, a project of the University of Wisconsin Law School's State Democracy Research Initiative, aims to make state constitutions and their commitment to democracy more accessible to researchers and the public.

A related SDRI project, 50constitutions.org, features the current, searchable text of all 50 state constitutions. SDRI also leads the project Tracking Constitutional Change, which displays how state constitutions have developed and changed over time.

Go to: The Democracy Principle Essay — Categories — Methodology

The Democracy Principle

Democracy in the United States today faces serious challenges. At both the state and national levels, commentators worry about attacks on voting rights, the warping of representative institutions through gerrymandering, and unstable transfers of power. They wonder if we will continue to be a functioning democracy in the years to come.

The federal Constitution offers limited resources to address these problems, and it creates headwinds to majority rule through the structure of the Senate, Electoral College, and federal courts, as well as the difficulty of amendment. The U.S. Supreme Court has been decidedly unreceptive to claims that it must protect democracy; most prominently, it has declared that extreme partisan gerrymandering claims are not "properly suited for resolution by the federal courts."

State constitutions offer vital resources to combat antidemocratic action. Though often overlooked, these foundational documents are powerfully committed to democracy. In text, structure, and history alike, they privilege popular sovereignty, majority rule, and political equality. As a shorthand, state constitutions share a commitment to a democracy principle.

To see how the democracy principle arises, consider some core aspects of state constitutions:

- Forty-nine state constitutions expressly recognize popular sovereignty, commonly stating that "all political power is inherent in the people."

- Every state constitution affirmatively confers the right to vote, and a majority require that elections be "free," "free and equal," or "free and open."

- State constitutions closely link government institutions to the people, including by providing for the direct election of a range of officials—not just legislators but also executives and judges—without the skew of the U.S. Senate or the Electoral College.

- In turn, no state judiciary is as insulated from popular accountability as the U.S. Supreme Court. A supermajority of states elect high court judges in some fashion; most impose term limits or retirement ages; and none use appointment mechanisms that have the skew of the U.S. Senate or Electoral College.

- State constitutions require the government to act with a public purpose and to treat all members of the political community as equals.

- In nearly half the states, direct democracy provisions allow the people themselves to enact or reject statutes, amend their constitutions, and recall officials.

These provisions are no accident. State constitutions are products of ongoing revision by the people: Most states have held multiple constitutional conventions, and state constitutions collectively have been amended more than 7,500 times. The provisions underlying the democracy principle reflect deliberate popular efforts to push back against unrepresentative or ineffective government.

Many state court decisions have embraced the democracy principle. In recent years, state courts and constitutions have led the way in reining in extreme partisan gerrymandering. The high courts of Pennsylvania and Alaska have held unconstitutional extreme partisan gerrymanders, as did North Carolina's supreme court before it reversed course after the state's 2022 elections. More complicated decisions in New York and Ohio engage with those states' recent amendments seeking to limit gerrymandering—amendments that themselves show the democracy principle at work.

Looking beyond gerrymandering, recent decisions in Montana and Pennsylvania also embrace the democracy principle in rejecting changes to judicial elections and approving mail-in voting, respectively. So do decisions pushing back against legislative efforts to subvert popular initiatives. In 2021, for example, the Idaho Supreme Court invalidated a statute that would have made popular initiatives virtually impossible to qualify for the ballot— a statute spurred by the state's successful Medicaid expansion initiative. Attacks on popular amendment are also unfolding in other states, and the democracy principle can similarly inform challenges to those measures.

Of course, there are state court decisions that go the other way, like North Carolina's reversal on partisan gerrymandering and Mississippi's rejection of the popular initiative. But the democracy principle provides a reference point against which to measure such decisions and resources with which to respond.

This website offers researchers, students, journalists, and the public a primer on the state constitutional democracy principle. For more on what the site covers, see our methodology below. And for more on the democracy principle, including further details on its key pillars and historical origins, see these additional articles and essays. Although each state's expression of the democracy principle differs, every state constitution includes a set of provisions to ensure governance by popular majorities on equal terms. And even as states have not always lived up to the promise of the democracy principle, it has underwritten important advances over time. It must not be neglected today.

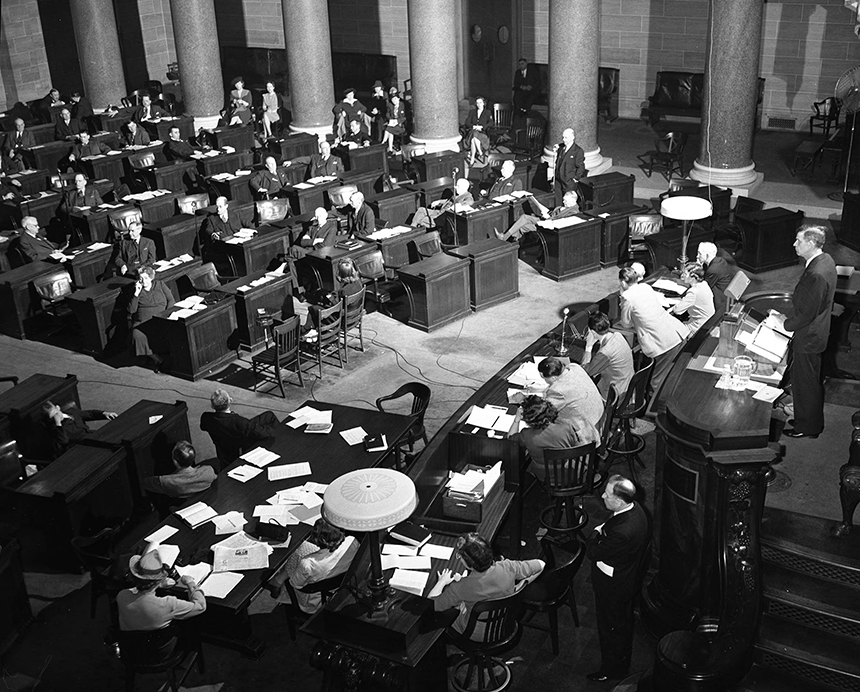

Image citations: Unidentified Montana Highway Department staff photographer, Photo # PAc 86-15.71218-02. Photographs from the Montana Historical Society; "Betty Babcock signing the Montana Constitution", Photographer Unknown, Photo # 952-217. Photographs from the Montana Historical Society; "Constitutional Convention, Missouri Constitution (1945)", Witman, Arthur (1902-1991), Photograph Addenda (S0717). S0717-10074. The State Historical Society of Missouri, Photograph Collection.

Categories

-

Popular Sovereignty

All state constitutions, except for New York, expressly state that the state's political power is inherent in the people, and many constitutions further describe popular power to alter or change the constitution. This category includes these provisions of popular self-rule.

-

Suffrage

All fifty state constitutions expressly provide for a right to vote, and many constitutions describe additional protections of voters or provide that elections must be "free and equal." This category includes each state's general right to vote, as well as any more specific protections.

-

Political Equality

State constitutions typically require the government to treat all members of the political community as equals, whether by requiring a public purpose to state expenditures, prohibiting private, special, and local laws, or by providing equal protection guarantees. This category includes these various equality provisions.

-

Government Institutions

When it comes to representative institutions, state constitutions forge strong connections between the people and their government by providing for direct election of an array of officials—not just legislators but also executives and judges—without the distortions of the U.S. Senate, the Electoral College, or judicial life tenure (except in Rhode Island). This category includes provisions that speak to the selection and structure of state government institutions

-

Direct Democracy

Roughly half of state constitutions permit the people to govern directly, including through popular initiatives, a popular vote on legislatively-referred referendums, or the recall of state officials. This category includes these mechanisms of direct popular governance.

-

Constitutional Change

State constitutions typically establish multiple mechanisms for amendment, allowing the people to continue to shape their founding documents over time. This category includes the various provisions—including popular initiative, legislatively referred amendment, and convention—that establish and explain state constitutional amendment.

Methodology

This website builds on research by Professors Jessica Bulman-Pozen and Miriam Seifter that has informed their academic articles and essays on state constitutions. Like Bulman-Pozen and Seifter's work, this site includes provisions that are distinctive to state constitutions and closely related to democracy, but does not exhaust the landscape of provisions that have shaped state democracy—including provisions on jury rights and education.

The team at the State Democracy Research Initiative did additional work to add, update, and organize relevant provisions. Where practical, the website includes the full text of a section. For certain categories, the website includes only an opening provision (like the establishment of a popular initiative right) but excludes the more detailed sections that follow. Researchers should use our site in conjunction with a constitution's full text.

Although the site is focused on constitutional text, two categories include protections that have been established primarily by case law. The general equality sub-category includes not only provisions with express "equal protection" language, but also other constitutional provisions that state supreme courts have relied upon to define a right to equal protection under the state constitution. Similarly, the public purpose sub-category includes cases that state courts have interpreted as establishing a public purpose requirement for state legislation.

The roughly two dozen featured state court decisions are cases that exemplify the democracy principle across varied subject areas, rather than a full appraisal of a state's case law. Indeed, state courts do not always live up to the promise of the democracy principle—but highlighting the cases that do so can help in assessing divergent decisions and provide resources with which to respond.